Geral Blanchard, LPC, is a psychotherapist who is university trained in psychology and anthropology. Formerly of Wyoming and currently residing in Iowa, Geral travels the world in search of ancient secrets that can augment the art and science of healing. From Western neuroscience to Amazonian shamanism, he has developed an understanding of how to combine old and new healing strategies to optimize recovery, whether from psychological or physical maladies.

MDMA and the Embodied Mind

If you have driven rural roads out West, specifically in cattle country, it’s likely you have rattled across a cattle guard every now and then.

I’m referring to steel cross bars elevated off the ground that are placed at the edge of a rancher’s land to keep cattle confined. An Angus will approach it sighting wide open spaces in front of it but will stop abruptly upon seeing the spaces between them. That two foot chasm beneath the bars distresses it and the cow turns around staying on its assigned land.

Then, if you take the offspring of that same Angus and never expose them to a cattle guard but instead paint horizontal lines on pavement near the boundary, they will turn back. In fact the cautionary imprint left on its mind gets passed on for several generations as if the cattle had always grown up around bona fide cattle guards, as if they are familiar with them.

At Tufts University School of Medicine, male mice exposed to chronic social instability and stress during adolescence transmitted stress-associated behaviors to their female offspring across for at least three generations even if they weren’t exposed to significant stress themselves, and never interacted with their fathers.

Offspring of Holocaust victims and progeny of the systematic abuse of Native Americans leaves an imprint as well. At the Mount Sinai School of Medicine a study looked at children of Holocaust survivors and noted they experienced the same hormonal abnormalities that were seen in direct survivors. Additionally, in the 1980s, Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart, a Lakota professor of social work, coined the term historical trauma. What she noted was “the cumulative emotional and psychological wounding over the life span and across generations” following colonization.

Other early studies of the intergenerational passage of trauma showed increased vulnerability to PTSD, distrust of the world, impaired parental function, chronic sorrow, an ever-present distrust and fear of danger, separation anxiety, boundary issues, and other psychiatric issues. And the influence of PTSD – spoken or unspoken – impacted children on biological and social levels.

Parents pass on genetic characteristics to their children BUT they also pass on acquired characteristics; that is epigenetic traits, especially if they originated in powerful and emotionally charged social experiences such as violence, separation, or the tragic loss of loved ones by oppressors.

The traumas leave an indelible imprint on genetic material in germ cells of individuals and can be transferred to their children, to their children’s children, etc.

So when a person feels chronically depressed and angry, deeply distrustful, prejudiced, filled with anxiety, and wears a defensive “body armor,” their search for trauma may begin but no evidence may be uncovered…at least in this generation. How confounding. Psychiatric patients may carry an amorphous and intractable wound that gets personalized and damages their self-esteem while their best therapeutic efforts do not reveal any discernable causal factors or yield results.

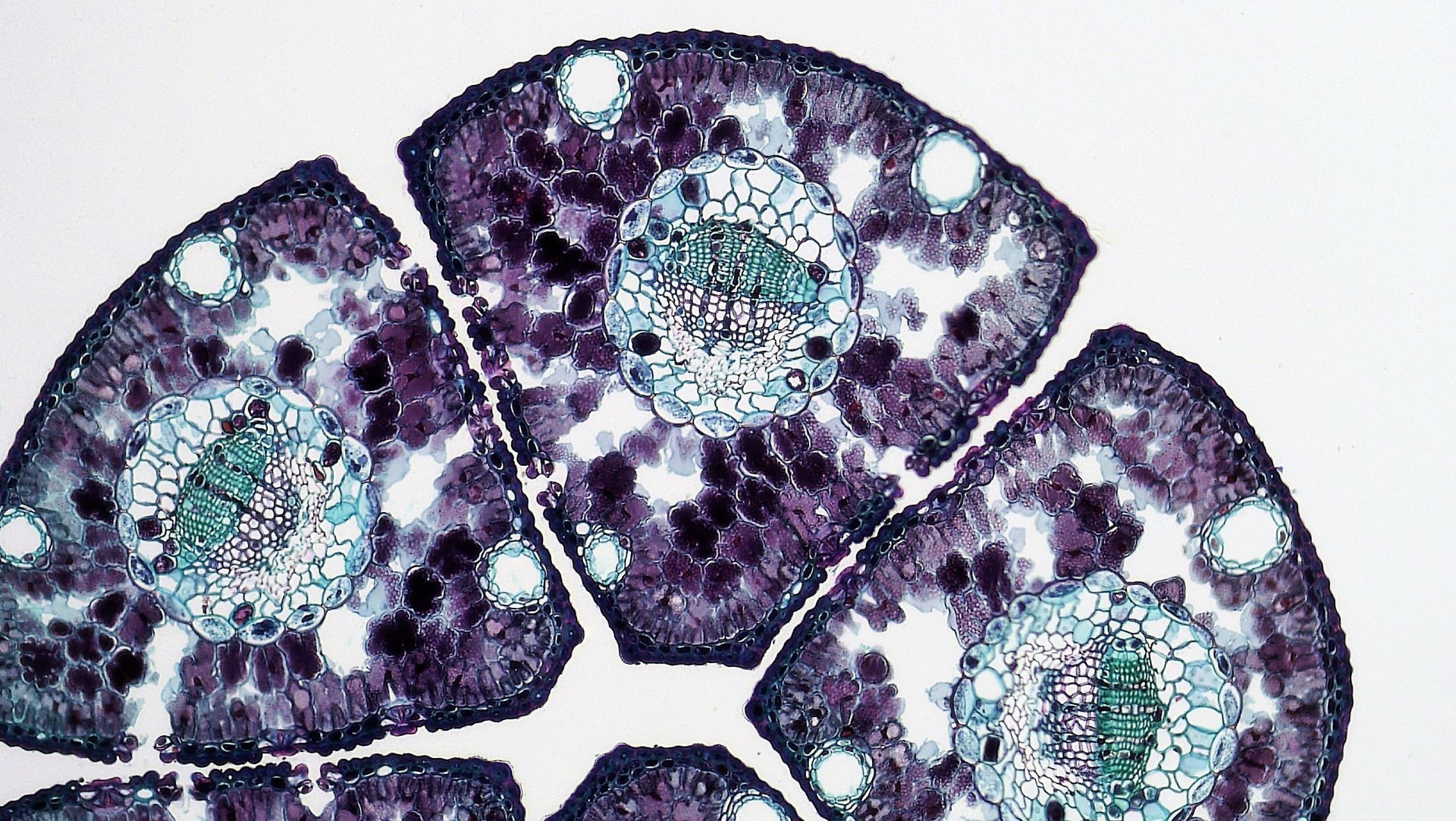

Bessel van der Kolk has renewed our interest in this phenomena in his best-selling book, The Body Keeps the Score. He was referring to cellular memory. More recently, in The Embodied Mind by Thomas Verney, M.D., he concludes there are brain centers throughout our body and the cranium may not be where memories are exclusively held; many are stored in our cells, bodywide, only to be released when we can handle it.

Verney’s book has many significant takeaways:

- The life experiences of parents and grandparents may impact the physical and emotional health of their descendants as if a trauma was directly experienced.

- Traumatic experiences of our ancestors can lead to extra sensitivity to future traumatic events when we react more strongly than expected.

- Genes don’t make us who we are. Gene expression (epigenetics) does. The expression is contingent upon the life we live. Our DNA is the cellular equivalent of the iCloud.

- When cells grow up they remember their childhoods, their conception, or even their parent’s childhoods.

- The bacterial community (biofilms) of our electrical intestines are capable of learning and remembering, much like the electrical transfer of information in our cranial brain.

- The heart, like the gut, contains an intrinsic nervous system that exhibits both short and long-term memory functions.

- What our ancestors didn’t face and resolve accumulates leaving us with pain that it is difficult to “put our finger on,” leaving us puzzled as to what to do about the deep and lasting sadness.

- Much of what happened in previous generations – shameful and unaddressed secrets – has left its mark locked in the cellular structure of the body. The body remembers better and longer than the cranial brain. Therefore body-oriented psychotherapy may be beneficial.

- Ideas about the heart that we carry in our collective unconscious, of it being the center of thought, feeling, and personality, are closer to modern science than previously postulated.

While MDMA is a heart brain and cranial brain medicine, no scientific evidence is available attesting to its effectiveness in resolving intergenerational trauma. Anecdotal accounts, however, are cautiously optimistic.

**********

“The universe is not only stranger than we think, but stranger than we can think.”

- Werner Heisenberg, Nobel Prize winner for the discovery of quantum mechanics

*********

Other Topics

Basics of MDMA

Rituals and Ceremony

Brain and MDMA

Trauma

Heart

Energy Movement

Quantum Physics

Native Cosmologies

Nature

Spirituality/Enlightenment

Kogi Tribe

Books written by Geral T. Blanchard

More Articles